Friday 29 August 2014

The Indefatigable Lithuanians

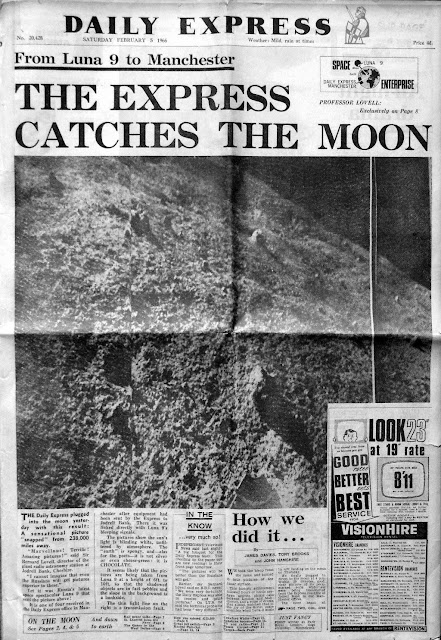

Sir Bernard Lovell and the Mind War

Fear And Loathing At The Watergate: Mr. Nixon Has Cashed His Check - by Dr. Hunter S.Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson: …You know, I was actually in the Watergate the night the bastards broke in. Of course, I missed the whole thing, but I was there. It still haunts me.

Playboy: What part of the Watergate were you in?

H.S.T.: I was in the bar.

Playboy: What kind of a reporter are you, anyway, in the bar?

H.S.T.: I’m not a reporter, I’m a writer.

Fear And Loathing At The Watergate: Mr. Nixon Has Cashed His Check

Part I: The Worm Turns in Swamptown ... Violent Talk at the National Affairs Desk ... A Narrow Escape for Tex Colson... Heavy Duty in The Bunker...No Room for Gonzo? 'Hell, They Already Have This Story Nailed Up and Bleeding from Every Extremity.'

"Reflecting on the meaning of the last presidential election, I have decided at this point in time that Mr. Nixon's landslide victory and my overwhelming defeat will probably prove to be of greater value to the nation than would the victory my supporters and I worked so hard to achieve. I think history may demonstrate that it was not only important that Mr. Nixon win and that I lose, but that the margin should be of stunning proportions... . The shattering Nixon landslide, and the even more shattering exposure of the corruption that surrounded him, have done more than I could have done in victory to awaken the nation... . This is not a comfortable conclusion for a self-confident — some would say self-righteous — politician to reach...."

— George McGovern in the Washington Post: Aug. 12th, 1973

Indeed. But we want to keep in mind that "comfortable" is a very relative word around Washington these days — with the vicious tentacles of "Watergate" ready to wrap themselves around almost anybody, at any moment — and when McGovern composed those eminently reasonable words in the study of his stylish home on the woodsy edge of Washington, he had no idea how close he'd just come to being made extremely "uncomfortable."

I have just finished making out a report addressed to somebody named Charles R. Roach, a claims examiner at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Headquarters of Avis Rent-a-Car in Arlington, Virginia. It has to do with a minor accident that occurred on Connecticut Avenue, in downtown Washington, shortly after George and his wife had bade farewell to the last staggering guests at the party he'd given on a hot summer night in July commemorating the first anniversary of his seizure of the presidential nomination in Miami.

The atmosphere of the party itself had been amazingly loose and pleasant. Two hundred people had been invited, — twice that many showed up — to celebrate what history will record, with at least a few asterisks, as one of the most disastrous presidential campaigns in American history. Midway in the evening I was standing on the patio, talking to Carl Wagner and Holly Mankiewicz, when the phone began ringing and whoever answered it came back with the news that President Nixon had just been admitted to the nearby Bethesda Naval Hospital with what was officially announced as "viral pneumonia."

Nobody believed it, of course. High-powered journalists like Jack Germond and Jules Witcover immediately seized the phones to find out what was really wrong with Nixon ... but the rest of us, no longer locked into deadlines or the fast-rising terrors of some tomorrow's election day, merely shrugged at the news and kept on drinking. There was nothing unusual, we felt, about Nixon caving in to some real or even psychosomatic illness. And if the truth was worse than the news ... well ... there would be nothing unusual about that either.

One of the smallest and noisiest contingents among the 200 invited guests was the handful of big-time journalists who'd spent most of last autumn dogging McGovern's every lame footstep along the campaign trail, while two third-string police reporters from the Washington Post were quietly putting together the biggest political story of 1972 or any other year — a story that had already exploded, by the time of McGovern's "anniversary" party, into a scandal that has even now burned a big hole for itself in every American history textbook written from 1973 till infinity.

One of the most extraordinary aspects of the Watergate story has been the way the press has handled it: What began in the summer of 1972 as one of the great media-bungles of the century has developed, by now, into what is probably the most thoroughly and most professionally covered story in the history of American journalism.

When I boomed into Washington last month to meet Steadman and set up the National Affairs Desk once again, I expected — or in retrospect I think I expected — to find the high-rolling newsmeisters of the capital press corps jabbering blindly among themselves, once again, in some stylish sector of reality far-removed from the Main Nerve of "the story" ... like climbing aboard Ed Muskie's Sunshine Special in the Florida primary and finding every media star in the nation sipping Bloody Marys and convinced they were riding the rails to Miami with "the candidate" ... or sitting down to lunch at the Sioux Falls Holiday Inn on election day with a half-dozen of the heaviest press wizards and coming away convinced that McGovern couldn't possibly lose by more than ten points.

My experience on the campaign trail in 1972 had not filled me with a real sense of awe, vis-a-vis the wisdom of the national press corps ... so I was seriously jolted, when I arrived in Washington, to find that the bastards had this Watergate story nailed up and bleeding from every extremity — from "Watergate" and all its twisted details, to ITT, the Vesco case, Nixon's lies about the financing for his San Clemente beach-mansion, and even the long-dormant "Agnew Scandal."

There was not a hell of a lot of room for a Gonzo journalist to operate in that high-tuned atmosphere. For the first time in memory, the Washington press corps was working very close to the peak of its awesome but normally dormant potential. The Washington Post has a half-dozen of the best reporters in America working every tangent of the Watergate story like wild-eyed junkies set adrift, with no warning, to find their next connection. The New York Times, badly blitzed on the story at first, called in hotrods from its bureaus all over the country to overcome the Post's early lead. Both Time's and Newsweek's Washington bureaus began scrambling feverishly to find new angles, new connections, new leaks and leads in this story that was unraveling so fast that nobody could stay on top of it... . And especially not the three (or four) TV networks, whose whole machinery was geared to visual action stories, rather than skillfully planted tips from faceless lawyers who called on private phones and then refused to say anything at all in front of the cameras.

The only standard-brand visual "action" in the Watergate story had happened at the very beginning — when the burglars were caught in the act by a squad of plain-clothes cops with drawn guns — and that happened so fast that there was not even a still photographer on hand, much less a TV camera.

The network news moguls are not hungry for stories involving weeks of dreary investigation and minimum camera possibilities — particularly at a time when almost every ranking TV correspondent in the country was assigned to one aspect or another of a presidential campaign that was still boiling feverishly when the Watergate break-in occurred on June 17th. The Miami conventions and the Eagleton fiasco kept the Watergate story backstage all that summer. Both the networks and the press had their "first teams" out on the campaign trail until long after the initial indictments — Liddy, Hunt, McCord, et al. — on September 15th. And by election day in November, the Watergate story seemed like old news.

It was rarely if ever mentioned among the press people following the campaign. A burglary at the Democratic National Headquarters seemed relatively minor, compared to the action in Miami. It was a "local" (Washington) story, and the "local staff" was handling it ... but I had no local staff, so I made the obvious choice.

Except on two occasions, and the first of these still haunts me. On the night of June 17th I spent most of the evening in the Watergate Hotel: From about eight o'clock until ten I was swimming laps in the indoor pool, and from 10:30 until a bit after 1:00 AM I was drinking tequila in the Watergate bar with Tom Quinn, a sports columnist for the now-defunct Washington Daily News.

Meanwhile, upstairs in room 214, Hunt and Liddy were already monitoring the break-in, by walkie-talkie, with ex-FBI agent Alfred Baldwin in his well-equipped spy-nest across Virginia Avenue in room 419 of the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge. Jim McCord had already taped the locks on two doors just underneath the bar in the Watergate garage, and it was probably just about the time that Quinn and I called for our last round of tequila that McCord and his team of Cubans moved into action — and got busted less than an hour later.

All this was happening less than 100 yards from where we were sitting in the bar, sucking limes and salt with our Sauza Gold and muttering darkly about the fate of Duane Thomas and the pigs who run the National Football League.

HUGHES, NIXON AND THE CIA: THE WATERGATE CONSPIRACY WOODWARD AND BERNSTEIN MISSED - an investigative report By Larry DuBois and Laurence Gonzales

HUGHES, NIXON AND THE CIA: THE WATERGATE CONSPIRACY WOODWARD AND BERNSTEIN MISSED

THE PUPPET AND THE PUPPETMASTERS

UNCOVERING THE SECRET WORLD OF NIXON, HUGHES AND THE CIA

including

The Buying of the President

The World's Biggest Intelligence Front

The War Within the Hughes Empire

The Untold Story Behind Watergate

Of all the mysteries surrounding the Watergate affair, perhaps the strangest is that in this, the most thoroughly investigated burglary in history, no publicly accepted motive for the break-in itself has ever been established. A vague notion that a group of Republican-sponsored burglars decided to get some dirt on the Democrats and did so without knocking is still widely believed. Lost in the bonanza of books and movies about who did it and how it was done is the central question: Why did it happen?

In the recent past, some accounts—notably, J. Anthony Lukas' massive Watergate study, "Nightmare"—have suggested that both the Howard Hughes organization and the CIA had connections with Watergate. And some important pieces of the puzzle were put in place by a few of the investigators on Sam Ervin's Senate Watergate committee. But the puzzle was never made whole, the pieces never seemed to fit.

A set of unusual circumstances led PLAYBOY to undertake an investigation of Hughes and the CIA and to get a fuller picture of Watergate. Part I of our report will examine the links between Hughes and the CIA and the events leading up to Watergate. Part II, to appear in November, will examine the cover-up that succeeded and will reveal how newsmen were misled in their efforts to report the whole story.

To sort of take the term Watergate and link

it to Howard Hughes, I think, is really unfair.

-BOB WOODWARD, April 25, 1976

IN THE SPRING OF 1975, a man named Virgino Gonzalez(no relation to Laurence Gonzales) drafted an affidavit that was executed in Mexico City. In the sworn document, he claims to be an ex—CIA agent who was assigned by the agency to monitor the activities of John Meier, a former Hughes executive. "At the end of 1971," Virgino Gonzalez wrote, "I was ordered to an assignment that included monitoring the activities of John Meier and was shown a file on him. . . . This file showed that Meier came from New York, his early business life and how he joined Hughes and evaluated the underground [nuclear] testing in Nevada. He was giving the AEC a hard time on behalf of Hughes."

Meier, a computer expert and environmentalist who had worked for Hughes off and on since 1959, was sent to Las Vegas by Hughes to evaluate environmental problems. Before Hughes moved to Vegas in November 1966, he wanted Meier to give him a full report on the effects of atomic testing at the Nevada Test Site, about 100 miles from the city. During three of Hughes's four years there (1966-1970), Meier was his scientific advisor and one of the few Hughes executives who communicated directly with the boss. Hughes had chosen Meier to handle his personal pet projects, such as his fierce campaign against nuclear testing. Secretly—not even known to others in the organization—Meier managed Hughes's investigations into areas that appealed to the farthest reaches of Hughes's imagination: parapsychology, LSD, mysticism, cryonics (the science of freezing human bodies with the hope of later reviving them) and other equally unlikely subjects.

Meier received the 1966 Aerospace Man of the Year award, the 1968 Nevada Governor's Award for Technical Achievement in Data Processing and was a member of President Nixon's Task Force on Resources and Environment. He was on the board of advisors of The Manhattan Tribune, was a member of the Governor's Gaming Industry Task Force and in 1971 was appointed special advisor on environmental affairs to Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska.

When Virgino Gonzalez filed his affidavit, a copy was flown to Los Angeles, where Meier's attorney, Robert Wyshak, was told in an anonymous phone call to pick it up at a hotel near the airport. Wyshak, former Assistant U. S. Attorney with experience as chief of the tax division of the Central District of California, determined to his satisfaction that the document was authentic and that Virgino Gonzalez was telling the truth about his illegal surveillance of Meier. He sent a copy to Meier and Meier sent a copy to Washington for examination by another attorney. It was intercepted en route—they believed by the CIA—and they then decided to file it in the U. S. district court in Nevada.

Wyshak provided PLAYBOY with a copy of the affidavit because of the last line, which reads, "I asked to be put elsewhere and was put onto Hugh Heffner [sic] for a time." The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (the Church committee) was unable to locate Virgino Gonzalez, or to confirm his employment by the agency, and views the affidavit with suspicion. We never found Gonzalez but did interview sources who claim to have had contact with him, including one writer who told us about interviewing Gonzalez on his agency activities. The authenticity of the document still remains in doubt, but there is strong circumstantial evidence indicating that the agency did spy on Meier, as Virgino Gonzalez claims.

What began as an attempt by us to determine the extent of illegal CIA surveillance of Hefner gradually developed into an investigation of the CIA itself. That search led us straight into the Hughes organization, where the story emerged of how critical Hughes had been in the rise and fall of Richard Nixon, how the CIA had gradually turned the Hughes companies into its largest front organization and how those interrelated matters were all part of the motive for the Watergate break-in.

John Meier1 is now a fugitive from the United States, living with his family in British Columbia under landed-immigrant status granted him by the Canadian government. He supports himself with part time consulting work for the Canadian government and private organizations while he fights his case. The reason he is a fugitive stems from an extremely complex legal case that began with an IRS indictment for back taxes on money he supposedly made from Hughes companies on mining deals. Meier claims he is innocent; the IRS claims to have a- strong case against him. The press has rarely mentioned Meier's name in connection with Watergate and most accounts of him have discussed only his alleged crime. As a result, we were reluctant to believe him at first. But more than 100 hours of interviews with him and hundreds of documents obtained by PLAYBOY during a year's research all point to one inescapable conclusion: On the subject of his role in events leading to Watergate, Meier is telling the truth, and his recall of detail rivals John Dean's.

_____________________________________________________________________________

1 Not to be confused with Johnny Meyer, a former Hughes aide who, in the late Forties, was involved in the Hughes military-contracts scandal that ended in a Senate investigation.

_____________________________________________________________________________

In a recent interview with us, Meier said, "I'm fully convinced that one big reason for the break-in wasn't to get something on McGovern but to find out what I was telling the friends of Larry O'Brien [the Democratic national chairman] about Richard and Don Nixon and Hughes, to see if anything was going to break before the election. They knew the Nixons were Hughes's greatest asset in getting his purchase of Air West airlines approved and that Hughes was fronting for the CIA; they knew I was talking to left-wingers, Democrats, McGovern people—people who scared the hell out of the agency and the White House."

Meier, at 42, is an intense, often obsessive man. He kept a meticulous diary of his Hughes years. Every phone call on Hughes's behalf, every flight number, every meeting is noted neatly in ballpoint pen in one of a dozen leather-bound "executive planners." One of his reasons for keeping these records was that the meetings, calls and flights involved Meier's dealings with some of the world's richest and most powerful men. He was, for example, Hughes's liaison to another reclusive billionaire, D. K. Ludwig, In Meier's six filing cabinets are hundreds of handwritten memos to and from Hughes, as well as internal White House memos, letters from various Government officials and political lobbyists and numerous in-house reports prepared for Hughes.

These documents and Meier's own accounts provided the key to the bits and pieces of information that are buried in the mass of publicly available information generated by Watergate—either in news reports or in court proceedings, in affidavits or in the transcript of the Watergate hearings. The picture that emerges shows the Hughes organization inextricably entangled in American politics, inside the White House and out. It shows the gradual merger of the Hughes organization and the CIA to such a point that it is difficult to determine where one ends and the other begins.

After Meier was indicted on August 9, 1973, he sought immunity in exchange for his story. He offered his testimony to the Watergate committee and was interviewed for 13 hours on October 13 and 22 of that year so that investigators could decide whether or not to take his testimony officially. According to the transcript of those sessions, Meier asked Watergate investigators, "Why not put the cards on the table about Hughes, Nixon and [Bebe] Rebozo? I have been shell-shocked from the IRS and Hughes. I told you that [John] Ehrlichman had me bugged and put the IRS on me. I don't have the organization behind me the President has or the money Hughes has. I'm fighting for my life and my family."

Meier's name is scattered throughout the Senate Watergate report, but he was never called to testify. His story seemed confusing and contradictory to investigators and they decided against granting him immunity. But the fact remains that most of the major targets of the investigation had significant ties to Hughes:

• Attorney General John Mitchell, overruling a prior decision of the Antitrust Division, had given Hughes permission to buy more than the five casinos he already owned in Las Vegas.

• E. Howard Hunt worked for Robert F. Bennett, who had the Hughes public-relations account in Washington. In February 1972, Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy had discussed with Hughes security chief Ralph Winte a plan to burglarize the offices of Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun.

• Nixon's confidant Bebe Rebozo was the bag man for Hughes's now famous $100,000 contribution to Nixon.

• Charles Colson had encouraged the White House to cultivate Bennett's friendship because of the financial and political clout Bennett's Hughes connection carried.

Meier tried to convince the Watergate investigators that he could prove himself a valuable witness. "I want to prove my statements to you," he told them, "I don't want to say it's my feeling Richard Nixon has money in the Bahamas.2 I want to say this is why, this is what I was told and this is who told me. These are serious charges. I don't want to talk in general, without having to prove what I'm saying."

_____________________________________________________________________________

2 The reference is to fugitive financier Robert Vesco, who successfully swindled at least $224,000,000 from a company named Investors Overseas Services, then moved to the Bahamas for a while. Two hundred thousand dollars he later secretly contributed to Nixon's 1972 campaign was used in part to finance the Watergate break-in.

_____________________________________________________________________________

At that point, Watergate investigator Scott Armstrong—who later worked on The Final Days with Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—explained to Meier, "We are not conducting an investigation of Summa [Hughes's holding company] or of Hughes. We are conducting an investigation of the 1972 campaign." That was, in fact, the Senate committee's mandate, but clearly, those were impossible ground rules, rather like investigating cancer over the telephone.

•

The relationship between Hughes and Nixon goes back at least to 1956. That year, Hughes lent Donald Nixon $205,000 to save a failing restaurant business. For Hughes, giving money in exchange for potential political favors was not unusual. Right after that loan—in a coincidence that investigators have been suspicious of for years—while Nixon was Vice-President, the Hughes Medical Institute was suddenly granted a tax-exempt status after prior refusals by the IRS. The loan to Donald was kept secret for obvious reasons. But four years later, one week before the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon election, columnist Drew Pearson got the story and printed it. The press flashed it across the country and to this day, Nixon and his friends believe it was the news of that loan that was partly responsible for his defeat by Kennedy.

In 1962, Nixon was running for governor of California. The loan again became a campaign issue and Nixon was called on to explain it publicly. Again he lost the race. Later, Rebozo's attorney, William Frates, was to say that Rebozo felt the story "had materially affected the outcome of the 1960 Presidential election and the 1962 governor's race in California." So not once but twice Nixon's relationship with Hughes was connected, at least in his mind and the minds of his friends, with agonizing political setbacks.

In 1968, Nixon was again running for President. Hughes had moved into his penthouse suite at Las Vegas' Desert Inn (known locally as the D.I.). Meier's files are jammed with photocopies of memos from that period, all of which had been handwritten with a ballpoint pen on lined yellow legal pads. Hughes didn't mince words when directing his executives to achieve his goals for him. In reference to political contributions that year, for example, he wrote to Robert Maheu, manager of the Hughes-Nevada Operations: "I want you to go see Nixon as my special confidential emissary. I feel there is a really valid possibility of a Republican victory this year. If that could be realized under our sponsorship and supervision every inch of the way, then we would be ready to follow with [Paul] Laxalt [Nevada's governor at the time] as our next candidate."

Frank statements like that, as well as court documents from lawsuits against Hughes, show that he desperately wanted four things at that time and was prepared to devote enormous resources to getting them.

1. He wanted to select a Presidential candidate of his own and "go all the way" in funding him.

2. He wanted to purchase an airline. He had been forced out of ownership of TWA and aviation had always been his first love. Air West was for sale and he was determined to buy it.

3. He wanted to expand his Las Vegas empire. He had bought five hotel-casinos and the Justice Department had ruled he could make no more purchases without violating its antitrust guidelines. Hughes's attitude was that Justice could go to hell.

4. With a fury that bordered on the pathological (see A Hughes Vignette on page 182), he wanted the Atomic Energy Commission to stop underground nuclear testing, which caused the D.I. to sway back and forth a few inches.

THE PURCHASE OF NIXON

I can make or break anybody.

- -HOWARD HUGHES

The last three problems could be solved much more easily if the first goal were accomplished. Maheu had initially convinced Hughes that Hubert H. Humphrey could take care of the AEC. Hughes wrote to Maheu in early 1968, "There is one man who can accomplish our objective through [Lyndon] Johnson—and that man is HHH. Why don't we get word to him on a basis of secrecy that is really, really reliable that we will give him immediately full, unlimited support for his campaign to enter the White House if he will just take this one on for us?"

It turned out that Humphrey wasn't altogether willing to go along with Hughes's plan. He wanted technical Information—conclusive scientific proof that the tests were as harmful and dangerous as Hughes claimed. Hughes had told Meier he didn't place much importance on the technical side—it was nice backup leverage, but he simply wanted, as he wrote, to "handle this just as if we were buying a hotel." In other words, paying for it was Hughes's idea of a solution. That is perfectly acceptable in buying a hotel, but when a Government decision turns on the deal, it is known as bribery.

Hughes chose Nixon and bribed him. The $100,000 he gave Rebozo for Nixon was well reported during the Watergate investigation. At least another $150,000 changed hands in subsequent years, some through Robert F. Bennett, who would later figure prominently in the Watergate affair. The New York Times reported on August 4, 1975, "Howard R. Hughes got his secret contract with the Central Intelligence Agency for the ship Glomar Explorer five weeks after making an `emergency' contribution of $100,000 to President Nixon's 1972 re-election campaign."

Meier claims to have discussed with Don Nixon possible Hughes contributions of sums much larger than the $100,000. Nobody has ever proved the money changed hands, but there were conversations in the summer of 1968 between Don, Meier, Rebozo and others that indicate that it was a definite possibility. Don wanted Rebozo out of it. Rebozo wanted Meier and Don out of it. There were difficulties with the logistics, but the attitudes—the expectations and intentions—were clearly aimed at making the deal work.

The sum total of Hughes's favors and contributions may never be known, but his generosity was rewarded. In April 1968, with Johnson in the White House, he wanted to buy the Stardust and other casino-hotels, but the Justice Department drew up a complaint against the proposed acquisitions. Hughes temporarily abandoned his plans, dropped back and regrouped for another attack. He hired Richard Danner in February 1969, just a few weeks after Nixon's inauguration. He was put in charge of the Frontier Hotel. But one reason for bringing him aboard was that he could act as go-between for Hughes and Nixon through Rebozo. Even Hughes couldn't just walk up to the White House and hand the President a bundle of cash. Danner was a friend of both Nixon and Rebozo, had been for 20 years and claimed he had introduced the two.

This wasn't cause for much concern in the Hughes organization. Maheu had written to Hughes as early as June 28, 1968 (when the Democrats were still in power), that there would be no problems. In a gleefully vicious memo, he reinforced what Hughes already knew about the Government:

You can bet your life that the Antitrust Division will live to regret their contemplated action. Yesterday they had "firsthand" evidence that we have many friends in Washington who truly believe in us. Today, they have received - many inquiries—including one from the chairman of the Judiciary Committee—and that is just the beginning. Howard Cannon [Senator from Nevada] called me this afternoon to inform me that he and Senator Bible [of Nevada] have been told all day long—by fellow Senators—that they can depend on full support and assistance in sustaining their position that we obtain the Stardust. Cannon stated that Justice was severely ridiculed. . . . In the meantime, I've been in touch with George Franklin [Las Vegas district attorney] and Governor Laxalt and they are both ready to challenge the department "singlehandedly."

Clearly, Hughes was at the zenith of his power. He could demand almost anything from the Government and expect to get it.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on December 17, 1975, "The Justice Department in a dramatic turnaround just three days before Nixon's 1969 inauguration agreed not to oppose Hughes's proposed acquisition of the Landmark, a Las Vegas hotel and casino. Only 28 days before, the same Justice Department had informed Hughes's attorneys ... that the Government intended to oppose in court any attempt by Hughes to acquire the Landmark on the ground that such a move would violate the antitrust laws."

On March 19, 1969, only two months after Nixon's inauguration, Danner met with Mitchell and was told that Hughes could buy more hotels. At the time, he wanted the Dunes. Mitchell said, "We see no problem." Later, Danner gave another $550,000 campaign contribution to Re-bozo, this time in cash from the Silver Slipper casino.

The acquisition of Air West was accomplished by an exchange of favors as well. Hughes told Meier just to keep Don and Richard Nixon happy and they'd get what they wanted as long as Hughes got Air West. It was agreed at the time that Hughes would hire Don in some executive capacity (though this never happened). Rebozo met with Maheu on Nixon's behalf and worked out a "deal with the President" (as Hughes put it to Meier), whereby Hughes would stop his four-year-long campaign against atomic testing if Nixon approved his purchase of Air West. It worked well for Hughes, because the AEC, under pressure, had already decided to move to Amchitka, Alaska, and Hughes didn't so much care whether or not they exploded atomic bombs, he just didn't want them set off near him.

The Hughes empire wrapped itself so totally in the upper echelons of the Nixon Administration that soon after his inauguration in 1969, Nixon offered to send his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, to Las Vegas to negotiate with Hughes on the AEC problem. Nixon told Maheu that Kissinger was willing to meet Hughes personally or, if that was not acceptable to Mr. Hughes, Kissinger would settle for a telephone call. Hughes refused. The White House was advised to deal with Maheu. The President already regarded Hughes as a foreign government of sorts—at least foreign enough to send his National Security Advisor to negotiate with the man who ran Las Vegas.

Clearly, Nixon hadn't been President long before he had a great deal to protect. The Hughes-Nixon relationship was so sensitive that the scope of it was even kept from people at high levels in the White House. And Nixon was going to some extraordinary lengths to protect himself. Photographs showing Meier with Donald Nixon and others at Orange County Airport in July 1969 were taken by the Secret Service and passed to Rebozo at the President's request. Rebozo was supposed to contact Maheu to have Meier fired or "kept out of things."

Meier was Hughes's liaison with Don Nixon, and the White House was understandably anxious about this arrangement. Those close to the Nixons would always remember the disastrous Hughes loan to Don. As Ehrlichman told an interviewer recently, "I was sort of responsible for the care and feeding of the President's brother Don, and Don seemed to have a sort of magnetic attraction to the Hughes organization and the Hughes people . . . and so I was continually being confronted with Don Nixon's involvement and continuing relationship with people who had been or were members of the Hughes organization . . . so I was always engaged in trying to extricate him from those kinds of things."

After carefully setting up his career and going through more than his share of troubles, one of the last things the President wanted was to have anyone learn how entangled his career had become with Hughes.

THE MAGIC BOX

Hughes was extremely anxious to

get himself into an alliance with the

CIA that would protect him from

investigation by other Government

agencies. -ROBERT MAHEU

A CIA cover organization is a strange and very useful thing. It's like having a magic box. You can put things in and you can take things out. You can take things out that you never put in and you can put things in that will never come out. Or you can get into the box yourself and go away somewhere—or perhaps go away forever. If the box is large enough, you can put an entire country inside it and no one will ever know.

The Hughes organization is such a box, the biggest and most useful of its kind. According to information given to us by a highly placed intelligence source, there is nothing else like it in the world, as far as intelligence fronts go. It is no secret to most foreign governments, most of which stand in awe of its ineffable, elegant vastness. From within this magic box, an important part of the United States' covert intelligence operations emanate. But by 1971, it had begun to crack. So much had been put into the box that things were beginning to come out. The magic was fading.

Hughes's alliance with the agency started as early as 1949. Only two years after the CIA got its charter, it began giving contracts to Hughes.

On April 1, 1975, The Washington Post reported, "Hughes Aircraft [HAC] has been mentioned as a potential hotbed of interrelationships with the CIA." The New York Times on March 20, 1975, quoted high Government officials as saying that HAC had been building satellites for intelligence purposes for years and "employs a number of high-ranking CIA and military men." As early as 1960, Maheu had Hughes's blessing in taking on one of the agency's most sensitive assignments: the assassination of Fidel Castro. Maheu worked out several unsuccessful plots with gangsters Sam Giancana and Johnny Roselli.

The affinity between Hughes and the agency was natural: America's most secretive billionaire and the most secretive part of America's Government. In a way, Hughes was a kind of modern-day Leonardo da Vinci, an eccentric genius who pushed to the cutting edge of the 20th Century, whether in early talking movies or in space satellites. Just after his death was reported, Newsweek quoted a top-ranking Washington intelligence official as saying, "Hughes gravitated into areas that other people refused to go into or didn't believe in." HAC pioneered the synchronous-orbit satellite, built the first Early Bird satellite and the Surveyor spacecraft that made the first soft landing on the moon and sent pictures back to NASA in preparation for the manned moon shots. Without Hughes's signal-amplifying microwave tubes, pictures from Mars would have been impossible. HAC is responsible for three-dimensional radar that is used for tracking hundreds of planes simultaneously. And the world's first operating laser arced across the labs of HAC. Laser weapons are now one of the hottest topics within the Pentagon—they may someday make nuclear weapons obsolete. The secrets of laser-weapon technology are so closely guarded that Pentagon insiders will discuss it only in state-of-the-art terms.

HAC became a leading Government electronics contractor with the building of an early fire-control system in 1948 and the Falcon air-to-air missile. During the Korean War, HAC was the only contractor of fire-control systems for Air Force interceptors. More recently, HAC built the entire ground-based defense systems for Japan, Belgium, Switzerland and NATO.

For years, Hughes Tool Company (Toolco—sold by Hughes in 1972) held a virtual monopoly on mining-drill bits. (On the subject of whether or not he really did have a monopoly, Hughes once said, "We don't have a monopoly. People who want to drill for oil and not use the Hughes bit can always use a pick and shovel.") A highly placed intelligence source told PLAYBOY that this monopoly was one of the important factors in the relationship between Hughes and the CIA because of the importance of resource-recovery information to the agency. What this means is that any time someone drilled into the ground, the information about what was down there went straight back to the agency. The setup with Toolco had put the agency in a position of awesome power with respect to other countries' abilities to keep the exact nature of their resources confidential.

Over the past decade, according to Time, the Hughes organization received at least six billion dollars in secret CIA contracts. That's approximately $11,500,000 a week, over and above $11,500,000 a week in public Government contracts awarded to Hughes. That is about 1.2 billion dollars a year. Put another way, the Glomar Explorer, the Hughes-CIA secret ship that cost $343,000,000 to build and made headlines in 1974 for trying to raise a sunken Russian sub, was to CIA funding of Hughes as six cents is to a dollar.

The one Hughes operation that doesn't seem likely to be involved in these types of dealings is the Hughes Medical Institute, established in 1953 "for the benefit of mankind." The Miami-based tax-exempt foundation has as its stated purpose medical research. Hughes turned over to the H.M.I. all HAC stock and 50 percent of Theta cable TV—assets worth hundreds of millions of dollars—to support that purpose.

But, as with all explanations of Hughes's actions, behind that story is another story: Mismanagement of HAC had upset the Air Force so much that Secretary Harold Talbot threatened to cancel all HAC contracts if the problems weren't taken care of. This was done on December 17, 1953, by Hughes's donating HAC to H.M.I. and naming himself sole trustee of H.M.I. Apparently, that satisfied the Air Force, because HAC now has an annual cash flow in excess of $900,000,000. (Despite the enormous assets it owns, H.M.I. grants only about $1,500,000 a year in medical-research funds.)

Hughes had said for years that when he died, he intended to leave his entire estate to H.M.I. Meier claims that Hughes instructed him to meet with the institute's president, Ken Wright, to discuss the institute's relationship with the CIA and that on March 8, 1969, Wright told him it was really a CIA front doing only token amounts of medical research in order to protect its tax-exempt status. According to Meier, H.M.I. had taken a long lease on Cay Sal, an uninhabited Bahamian out island 40 miles north of Cuba, to provide a site for covert CIA training operations. Meier's story that the medical institute is actually a CIA front was corroborated recently when a former Pentagon official was quoted in Time as saying that HAC (solely owned by H.M.I.) "is a captive company of the CIA. Their interests are completely merged." In other words, if Hughes left his fortune to H.M.I., control of his whole empire would legally—and secretly—pass to the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA could then—under the guise of tax-exempt charity—fund any project, any covert activity imaginable, working its magic with billions of untraceable dollars through the seemingly legitimate channels of the Hughes empire.

Making Hughes's other companies nearly as attractive to the CIA was the fact that he was personally the sole owner of them. The sleight of hand with billions of dollars was not subject to the scrutiny publicly held corporations come under. And—aside from the obvious money, security and benefits—making the CIA attractive for Hughes was the fact that he was a fiery anti-Communist and a superpatriot.

Charles Colson has said that "Hughes is the CIA's largest contractor." In this position, Hughes had another advantage. He could hire its influential people for his own team.

Scores of high-level officials from Government intelligence and investigative agencies have moved over to the Hughes organization. A. D. "Bud" Wheelon left his position as deputy director of science and technology for the CIA to become president of HAC. At the age of 48, a three-star general named Ed Nigro was in line for the position of deputy director of plans for the Pentagon. He turned it down, ended his promising military career and went to work managing hotels in Las Vegas for Hughes. When questioned by reporters on this strange career tactic, Nigro commented, "I felt I could come out here and still serve my country." (Hughes wrote a memo to Maheu suggesting that Nigro could use his contacts in the Pentagon "to keep the Vietnam war going," in order to allow HAC to sell more helicopters.)

Robert Peloquin resigned as head of the Justice Department's organized-crime strike force and started what has become the world's largest private security company, Intertel. Hughes quickly became one of Intertel's most prominent clients'.

In turn, Toolco and HAC routinely hired CIA agents, who would then be given jobs in other countries. Meier first learned of Hughes's involvement with the agency in 1968. On August fifth, Maheu told Meier that a man named Michael Merhage, a new young Toolco executive, would be handling some business in South America. Meier was asked if he would use his contacts in Ecuador to open the right doors for Merhage. It was a routine request and Meier handled it in a routine way. He flew to Quito before Merhage arrived and explained to his friends in high government positions the importance of giving Merhage all the help he needed.

Meier returned to Vegas and when they met there, Merhage began explaining to Meier how really important this particular project was from an agency standpoint, believing Meier knew he was an agent using Toolco as cover. Meier was stunned by the revelation. (Merhage was apparently just a clumsy agent. In Meier's file on the Ecuadorian situation is a letter from a bemused Ecuadorian official explaining that Merhage "was so obvious" they spotted him as an agent almost immediately.) While Merhage was still in Nevada, he again let Meier in on an agency matter that should have been kept confidential, and this time it proved to be a serious mistake. He gave him a list of American politicians the CIA wanted funded through Hughes. Meier was supposed to act as a courier and give the directive to Hughes, but later the agency would suspect that Meier had retained a copy of the list. He did keep a copy, which PLAYBOY now has.

The directive is dated September 2, 1968. It is addressed to H.R.H., with a copy designated for R.M.A.—Robert Maheu Associates—and is headed "Proposed Fund-Support List as Through Local Outlets."

In the directive is our current President, Gerald Ford (then a Congressman from Michigan). The list reads as follows:

Paul J. Fannin, Arizona

Wilbur D. Mills, Arkansas

Craig Hosmer, California

Robert L. Leggett, California

Gordon L. Allott, Colorado

J. Herbert Burke, Florida

Hiram L. Fong, Hawaii

Larry Winn, Jr., Kansas

Joe D. Waggonner, Jr., Louisiana

Gerald R. Ford, Michigan

James 0. Eastland, Mississippi

William J. Randall, Missouri

Strom Thurmond, South Carolina

Dan H. Kuykendall, Tennessee

James H. Quillen, Tennessee

James M. Collins, Texas

Olin E. Teague, Texas

Omar Burleson, Texas

Abraham Kazen, Texas

We have been unable to determine why the CIA selected this particular group or to get any indication of whether or not they were aware that the agency had chosen them for funding. But the depth of CIA influence can be partly measured by the behavior of new, middle-level executives such as Merhage. When he didn't get a quick enough response to the funding directive, he gave another copy to Meier and this time wrote, "John—am asking for progress," and signed it.

The diplomatic relationship between Hughes and the American Government had clearly become extremely delicate, and only a very select group of people knew it was so deep and so broad that it even included the intelligence apparatus as its critical component. The press, the public, the FBI, the IRS, Congress—all of them were necessarily ignorant of the gravity of the relationship between Hughes and the agency and what it meant.

Even among Government insiders, it couldn't become common knowledge that the Hughes organization was in possession of some of the nation's most explosive national-security secrets, ranging from attempts to assassinate foreign leaders to the Glomar (see Shallow Throat on page 183) to the secret funding of American politicians by the CIA, using Hughes as the conduit for these funds.

With adventures like these on their hands, it was clearly imperative for agency officials to keep a very tight rein on any information about the inner workings of the Hughes-agency merger.3

______________________________________________________________________________

3 It was so important that the details of this merger not come out that in June 1974, three days after several documents that touched on the CIA links were subpoenaed by the Justice Department for the Securities and Exchange Commission, a group of highly professional burglars broke into Summa headquarters and removed those documents. According to several sources with firsthand knowledge of the case, this was a CIA job done to protect the Hughes-CIA relationship.

______________________________________________________________________________

Since other Government agencies were not aware of the extent of the relationship, investigations of Hughes's holdings could not be allowed to succeed.4 There was good reason for this. Any leaks could prove disastrous.

______________________________________________________________________________

4 For example, a 1973 Congressional investigation of tax-exempt foundations came up empty when it looked into H.M.I. During the course of the investigation, this exchange took place between Seymour Mintz, representing H.M.I., and Representative Ben B. Blackburn of Georgia:

BLACKBURN: [Howard Hughes] certainly has done well in mixing up his money. We cannot keep up with all the financial transactions. We have received a report, but our staff has had problems understanding all of these notes floating around and interest floating around mentioned in it. . . . Why can't that superb management pay off that note?

MINTZ: We have never made that demand on the Hughes Aircraft Company because we felt that it was not in the interest of the institute to hamstring the aircraft company to the point where it would be deprived of its working capital.

BLACKBURN: You mean Mr. Hughes, the trustee, has never felt that Mr. Hughes, the chief executive, ought to be hamstrung in paying Mr. Hughes the money Mr. Hughes owes Mr. Hughes?

______________________________________________________________________________

NIGHT OF THE LONG KNIVES

For quite a while, the security system seemed to be working very well. But in November 1970, a series of bizarre events took place that started cracking the shell of secrecy that had surrounded the operations for years. Exactly what took place in November 1970 is likely to remain a mystery. But it is certain that the date is crucial in beginning to comprehend Watergate and its aftermath.

An internal crisis had been brewing inside the Hughes empire since Howard's arrival in Las Vegas in 1966. During his years in Nevada, Howard Hughes the man was becoming separate from the Hughes companies, and his control of them gradually diminished. When he sold TWA, he received $546,549,711, and with it he built Hughes-Nevada Operations, putting Maheu in charge. But the rest of his multibillion-dollar empire was controlled by three executives outside Nevada. A woman named Nadine Henley, who had once been Hughes's personal secretary, had installed Ken Wright, one of her former chauffeurs, as president of the Hughes Medical Institute, and his first loyalty was to her.

In California, Toolco was controlled by a Mormon named Frank W. "Bill" Gay. He had maneuvered his way to a senior vice-presidency after beginning as the manager of Hughes's car pool. He was responsible for hiring the Mormon valets who surrounded Hughes day and night. They controlled the flow of information' into and out of his penthouse suite. With no word to the contrary forthcoming from Hughes himself, Gay was able to maintain his public image as that of a son to Hughes.

From New York, an attorney named Chester C. Davis handled much of the ongoing litigation involving Hughes, including the 12-year court battle over TWA. Davis, with his fiery tongue, dramatic gestures and shrewd maneuvering, has a well-earned reputation as just about the meanest man in any courtroom. (During the Watergate testimony, Davis represented Danner, who had delivered the now famous $100,000 to Rebozo. Davis personally steam-rolled over many of the investigators' questions. At one point, when Danner tried to add to Davis' own remarks, Davis growled: "You open that mouth again and you're going to have to go see a dentist." The court reporter dutifully typed it into the record.)

Davis, Henley and Gay had won control over the Hughes empire outside Nevada, but they had no proximity to Hughes; Hughes directed the Nevada Operations through Maheu and was in

constant communication with him via memos and phone calls. Maheu's ambitions represented a very real threat to Davis, Henley and Gay.

During the Nevada period, Howard's orders outside Nevada were frequently ignored. He could have his little halfbillion-dollar playground in Nevada, but Gay, Davis and Henley directed the course of serious world-wide business for the empire. Both Maheu and Meier witnessed Howard's gradual loss of control.

It is not easy to imagine how Hughes could own his empire outright and not have solid control over it. But he was a very unusual man. It is easy to forget that in 1953, he legally stepped down when he passed control of HAC to the institute to take his name off the books as official head of that company to smooth over the mismanagement problems he was having with the Air Force. This maneuver was designed to allow Howard to maintain control of HAC while satisfying the military that someone else was in charge. Later, his fear of germs, of kidnaping, of court subpoenas would seal him off from the outside world and make him dependent on a small group of Mormon aides for everything from food and medical attention to news from the real world. It was a simple matter for them to see that written communications to Hughes about the course of business in his empire did not escape their attention—or their censorship. Even Maheu was never allowed to meet Hughes face to face.

Aside from Maheu and the Mormon valets, one of the few people who spoke with Hughes on the phone regularly was Meier. His position was unique. Maheu and the other executives ran the Hughes-Nevada businesses; Meier handled the projects personally important to Hughes.

Hughes also involved Meier in some of his political and business projects, including the acquisition of Air West, the purchase of several mining claims in Nevada and Hughes's extremely delicate dealings with Donald Nixon.

In November 1969, Meier officially resigned his position with Hughes to set up the Nevada Environmental Foundation. Secretly, he continued to carry out assignments for Hughes.

But by 1970, Howard Hughes was a very sick man, and in early November, he was near death. His health had been failing since his mysterious operation in Boston in 1966, after which be had moved to Las Vegas. Now his weight was down to about 100 pounds, he was suffering from anemia and pneumonia and his hemoglobin count was down to four. This condition causes euphoria and erratic behavior. Normal hemoglobin is between 14 and 18 grams per 100 milliliters of blood. One of the doctors who attended him in his penthouse later told police his condition was so poor they feared for his life if he did not get to a hospital's intensive-care unit. For unknown reasons, Hughes remained in his suite. His memos and phone calls to Maheu and Meier, which had been tapering off since September, abruptly stopped in mid-November. On or about November 25, 1970, Thanksgiving eve, he suddenly vanished, having methodically worked to take over not only the city of Las Vegas but the entire state of Nevada. Hughes's Mormon valets put out the story that a smiling, healthy, high-spirited Howard R. Hughes had sashayed down nine flights of stairs at the back of the D.I., climbed into a limo and been winged away on a long-overdue and well-deserved vacation.

He enjoyed the flight, they said.

A number of media people took that jaunty-departure story at face value. Time's report began, "A few minutes before ten o'clock on Thanksgiving eve, Howard Hughes pulled an old sweater over the white shirt that he wore open at the neck, donned a fedora and walked to the rear of the penthouse atop the Desert Inn. . . . Hughes eased his tall, thin frame through a long-unused fire door and walked the nine stories down an interior fire escape to the hotel parking lot."

It's a nice picture, but neither Maheu nor Meier believed it for a second. They claim instead that an emaciated Hughes was carried out by Intertel agents, who sent a decoy caravan of limousines to the Las Vegas airport while Hughes was taken to Nellis Air Force Base and flown away in a Lockheed Jet Star. (According to an account in Look, by Benjamin Schemmer, editor of The Armed Forces Journal, Hughes was on a stretcher when he was loaded on the plane, and the flight crew that departed from Nellis was told, "Your life depends on your not looking to the rear.")

As mentioned before, what took place on November 25, 1970, may remain a secret, and there are only fragmentary reports on Hughes's actual condition. If he did throw on some old clothes and walk down nine flights of stairs, however, it represented a remarkable recovery from his condition earlier that month.

Meier had strong circumstantial evidence to support his belief that whatever happened that night, Hughes was no longer in control. On October 28, 1970, Meier and his wife had arrived in Honolulu and checked into the Kahala Hilton Hotel. They were joined there the next day by Donald Nixon and his wife. Both couples were vacationing at Hughes's expense, but Meier says he was also negotiating with Don about a high-level job for him in the Hughes empire. Hughes was eager to find Don a position and was keeping in touch with Meier by phone. On November third, a friend of Meier's named Mike O'Callaghan, in an upset victory (not expected or funded by Hughes), won the governorship of Nevada. Hughes called Meier the same day and instructed him to fly back immediately and begin to cement a sympathetic relationship with the new governor. Meier went to see O'Callaghan and on November 12 returned to Honolulu with Mr. and Mrs. O'Callaghan, who stayed until November 15. Meier sent his report to Hughes on November 16 and was told he would receive a prompt return call from Hughes, whose Nevada Operations had always run smoother with the good will of the governor. The call never came. Either Hughes was no longer functioning, Meier concluded, or he had suddenly lost interest in the President's brother and Nevada's new governor.

Maheu was not even told of Hughes's disappearance until December fourth, when, in a dramatic scene resembling a South American coup d'etat, a strike force of Intertel agents swooped down on Maheu's offices, physically ejected him and his staff into the street, locked and guarded the offices and files and seized control of the Hughes-Nevada Operations in the name of Gay, Davis and Henley.

Literally, one minute Maheu was in his office, carrying on with Howard's business; the next, he was on the street, having been told that he was relieved of all authority, including the authority to continue drawing the $500,000-a-year retainer he had been charging Hughes.

Maheu had evidence that Hughes had been kidnaped. He knew that Gay had long been on the outs with Hughes, despite the father-son image. One memo later circulated by Maheu expressed Hughes's opinion that Gay was responsible for the breakup of Hughes's marriage to Jean Peters. "I feel he let me down utterly, totally, completely," Hughes wrote. He added, "If I were to list all the grievances, it would fill several pages," In another memo to Maheu, dated March 21, 1968, Hughes had written of Gay, "Apparently you are not aware that the path of true friendship in this case has not been a bilateral affair. I thought when we came here and I told you not to invite Bill up here and not to permit him to be privy to our activities, you had realized that I no longer trusted him. . . . My bill of complaints against Bill's conduct goes back a long way and cuts very deep. Also, it includes a very substantial amount of money, enough to take care of any needs of his children several times over." Meier was also aware of Hughes's dislike for Gay. He explained that the money reference is to Hughes Dynamics, a computer-software company Gay had set up in the early Sixties without Hughes's knowledge or approval. Gay had spent millions of dollars hiring a staff of computer experts, who, according to documents in Meier's files, prepared studies on the computerization of such institutions as police departments and the U. S. Postal Service. Hughes Dynamics had also assisted the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City, at Hughes's expense, in beginning to computerize its operations. "They had offices all over the States, hundreds of people, they were spending millions of Hughes's dollars," says Meier, who was on the staff of Hughes Dynamics himself until he was tipped off that Hughes was not even aware of the operation and advised that he should get out. Meier resigned, and not long after that, Hughes's wife saw a TV news story about Hughes Dynamics and reported it to Hughes, who ordered the entire staff fired within 24 hours.

That was not the first time he had fired Gay. But each time, Gay managed to find a way around the order. Hughes had also sent Maheu a memo giving him "full authority" to take over the TWA case from Davis, which Maheu had attempted to do. On November 12, 1970—two weeks before Hughes's disappearance—in a three-page teletyped message to Davis, Maheu charged him with mismanagement of the TWA court case. Maheu wrote, "I must insist that you now step aside." Two days later, Davis drafted a proxy turning over control of the Hughes-Nevada Operations to himself and Gay. On the afternoon of November 14, 1970, according to Levar Myler and Howard Eckersley, two of Hughes's Mormon valets, they handed the proxy to Hughes for his signature. Myler served as witness; Eckersley, a notary public, sealed the proxy, which was then used as the legal basis for ousting Maheu. Both men had been hired by Gay to attend Hughes.5

______________________________________________________________________________

5 A few months after Hughes's disappearance, Eckersley, after years of laboring anonymously as chief staff executive for Hughes, showed up in Montreal touting a new mining stock called Pan American Mines Ltd. and implying that it was a Hughes venture. The stock quickly shot up 500 percent before Toolco announced that the venture was not backed by Hughes. The Canadian government indicted Eckersley for stock fraud. He remained in his position in the Hughes organization.

______________________________________________________________________________

Shortly after the take-over, Davis and Gay made public a "Dear Chester and Bill" letter from Hughes reiterating his desire to remove Maheu and ordering them to get the Maheu affair over with as quickly as possible. It is signed "Howard R. Hughes" and his fingerprints appear at the bottom of the page. At the very least, Maheu thought the letter was suspicious because Hughes did not begin his written communications to executives with "Dear." He began directly with a first name, such as "Bob—," or "John—." Nor did he sign personal messages "Howard R. Hughes." He signed them "H" or "Howard." The purpose of the fingerprints was to prove Hughes had written the letter. But curiously, sheriff's police captain William Witte of Clark County in Nevada later testified about those fingerprints: "From the way the latent prints developed on the three separate examinations, we feel it is impossible to tell how [emphasis added] those prints were placed on that piece of paper."

A BEAST WITH TWO HEADS

But whether or not Hughes was in control at the moment his fingerprints were placed on that letter, the meaning of the 1970 coup was that Maheu and Meier, the two men who knew intimately the inner workings of the Hughes empire, were convinced that Hughes was no longer calling the shots; and hostile actions taken toward them, in Hughes's name, made them bitter enemies of the new regime practically overnight. Powerful executives who are accustomed to having the nation's business and political elite seek their favor do not simply fade quietly into the background when they believe—rightly or wrongly—that an illegal coup has taken place and they are its victims, abruptly and ignominiously thrown out onto the street and made to look like fools. Together, Maheu and Meier had enough information to topple the entire structure involving the Nixon White House, the Hughes empire, the CIA and politicians from both parties who were secretly indebted to Hughes in ways that could cause a public outrage.

Ironically, the initial White House response to the Hughes upheaval was jubilant. Maheu had retained Larry O'Brien, for some of the Hughes public-relations work in Washington. Once Maheu was out, so was O'Brien—no friend to the Republican White House. The powerful Hughes account was turned over to Robert F. Bennett, who was, like Bill Gay, a Mormon. Bennett purchased Mullen & Company, a public-relations firm that also served as a CIA front organization, and which employed E. Howard Hunt. On January 15, 1971, Charles Colson wrote to another White House aide: "Bob Bennett, son of Senator Wallace Bennett of Utah, has just [taken] over the Mullen public-relations firm here in Washington. Bob is a trusted loyalist and good friend. We intend to use him on a variety of outside projects. One of Bob's new clients is Howard Hughes. I'm sure I need not explain the political implications of having Hughes's affairs handled here in Washington by a close friend. As you know, Larry O'Brien has been the principal Hughes man in Washington. This move could signal quite a shift in terms of the politics and money that Hughes represents."

But already there was concern about the dangers posed by the angry Maheu's relationship with O'Brien. A White House memo dated January 26, 1971, from Dean to H. R. Haldeman, says: "I have also been informed by a source of Jack Caulfield's that O'Brien and Maheu are longtime friends from the Boston area. . . . Bebe [Rebozo] is under the impression that Maheu had a good bit of freedom with Hughes's money when running the Nevada operation. Bebe further indicated that he felt he could acquire some documentation of this fact if given a little time and that he would proceed to try to get any information he could. He also requested that if any action be taken with regard to Hughes that he be notified because of his familiarity with the delicacy of the relationships as a result of his own dealings with the Hughes people." (The "delicacy" Rebozo referred to is not hard to understand. At that moment, he had $100,000 of Hughes's money that he had never reported to the IRS stashed in a safe-deposit box.) Two days later, Haldeman instructed Dean to get more information on Maheu and O'Brien: "You and Chuck Colson should get together and come up with a way to leak the appropriate information. . . . However, we should keep Bob Bennett and Bebe out of it at all costs."

In other words, the White House was looking for information to embarrass O'Brien because of his Hughes connection, but before long, it started to look like the change of command in the Hughes empire was going to threaten the White House far more than O'Brien. Maheu and Meier would see to that.

It was an odd couple that set out to destroy the new Hughes regime. Maheu was an ex–FBI agent who worked for the CIA while on the Hughes payroll and was instrumental in creating the role of CIA front for the Hughes empire; Meier was a computer expert who was more interested in cleaning up the environment than in planting spies overseas. Maheu and Meier had probably not seen eye to eye on anything important until they came to the same conclusion about Davis and Gay's take-over of the Hughes organization. For once, their hands were forced in the same direction.

Maheu began by taking his grievances into court, letting out bits and pieces of information. Meier began by talking to his friends—liberals, Democrats, journalists—about such things as Air West. Maheu and Meier both talked with columnist Jack Anderson. The conversations resulted in articles that were potentially more disastrous for both the Hughes people and, the White House than the column by Drew Pearson, Anderson's predecessor, about the 1956 loan. Anderson, for example, was the first to print, in August 1971, the outline of the $100,000 payoff to Nixon through Rebozo.

Haldeman wanted Rebozo kept out of it "at all costs," and now Anderson was bringing him into it. Anderson told PLAYBOY: "That column, and every other column I wrote about Hughes and Nixon, provoked a reaction so much stronger than on any other subject I could write about. They went crazy over there whenever I linked them to Howard Hughes. And I learned from sources in the White House inner circle that they believed the source for that column about the $100,000 to Rebozo was Larry O'Brien. They were mistaken, but they were convinced at the time that I was getting my stuff on Hughes and Nixon from Larry O'Brien."

The tension gradually increased through 1971. Maheu and Meier talked more and more. The agency, the Hughes empire and the White House became more and more concerned. In the Watergate testimony, several witnesses alluded to their nervousness about the struggle within the Hughes organization and its potential for serious political embarrassment.

In early 1972, the Clifford Irving biography of Hughes surfaced in the press as a fraud, prompting an unprecedented phone call from either Hughes or a man purporting to be Hughes. The reason for suspicion about the identity of the man making the call is the fact that he couldn't answer several of the identifying questions put to him by reporters who supposedly had known him. In the four-hour conversation, the voice rambled disjointedly, going into extended discourses on such topics as the way in which he trimmed his fingernails and the advantages of a clipper over a scissors. At one point, the voice said, Maheu "robbed me blind," sending Maheu into a rage that ended in a $17,300,000 defamation suit against Summa. In the course of this action, a very angry Maheu began telling even more about the internal workings of the organization as they related to Nixon and the CIA:

• He presented a tape recording of a phone call from Hughes, who told him in reference to a possible move to the Bahamas, "If I were to make this move, I would expect you to wrap up that government down there to a point where it will be, well, a captive entity in every way."

• July 4, 1972, Maheu gave the first detailed account of the famous $100,000 gift to Nixon—in a sworn deposition. While there had been some question before, Maheu now stated conclusively that the money was unquestionably meant for Nixon.

• He revealed that approval for Hughes's purchase of additional casinos was a favor granted by Nixon implying that Hughes had bought Nixon off.

• He described showing Hughes executive Ray Holliday the Hughes memo asking Maheu to give Lyndon Johnson the $1,000,000 bribe to stop atomic tests. "Mr. Holliday," Maheu said under oath, "dropped the yellow sheet of paper to the floor and requested of me whether or not his fingerprints could be taken off the piece of paper."

Although some of this was to take place after the Watergate break-in, its general impact gives an idea of how far Maheu was willing to go. He had apparently decided to pull out all the stops and blast the organization.

In some ways, Meier represented even more of a threat, especially to the White House. His close friendship with Don Nixon, as mentioned before, had long been a source of concern for the President. Although Donald and Meier were told at various points to keep away from each other, Don wanted to maintain his Hughes connection and Meier had a job to do. Meier, after all, was charged by Hughes with handling business dealings with Don. Don later testified to the Watergate committee that he viewed Meier as "the number-two man with Hughes." The Secret Service had already tapped Don's telephone because of his connections with Hughes, and as early as July 1969, the Secret Service had, as mentioned, photographed Meier and Don at the Orange County Airport, prompting an angry call to Don from Rebozo. But Don persisted in seeing Meier, which led to yet another embarrassing column by Anderson. Meier was going to have lunch with George Clifford, an Anderson investigator, and Don joined them, only to start bragging about his international wheeling-dealing. A February 11, 1972, Anderson column reads, "Suddenly he fixed his gaze on a visitor [Meier] connected with the airline Air West. 'How do I get Air West?' Donald demanded. 'We ought to do their catering. They owe me that.' " The story "upset the entire Nixon family," according to Meier, who was told that by Don.

Just the seamier aspects of the Air West story were enough to threaten Nixon's chances of re-election. Nixon hadn't forgotten the disasters of 1960 and 1962, caused by the Nixon family's relationship with Hughes, and in early 1972, his old nightmare was showing signs of repeating itself, and all because of the fallout from the internal Hughes explosion. On February third, The New York Times added a new dimension by carrying a story saying that Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun had a safe full of Hughes memos. One day later, Mitchell met with Liddy and the result was Liddy's belief that he had the go-ahead for two missions: the burglary of Greenspun's safe and a mission into O'Brien's office at the Watergate.

•

Friends throughout the Hughes organization had warned Meier not to get into politics after the 1970 blowup. He was told the organization would "ruin" him if he did. Meier ignored them, determined to get to the bottom of what he regarded as the mysterious disappearance of Hughes and to get on with his own career, now that he'd lost his position with Hughes. He decided to run for the U. S. Senate from New Mexico against an old friend of Nixon's, Pete Domenici. Meier announced his candidacy on January 11, 1972, and as the election year started, the White House had cause for alarm at Meier's conversations not only with Jack Anderson but with high-level McGovern supporters as well.

"I was telling them," Meier says, "that my feeling was that McGovern stood a chance of winning the election only if he exposed Nixon in areas such as his relationship with Hughes, such as the fact that I was told directly by Hughes to lay off the AEC because he had a deal with the President that he would get approval for the acquisition of Air West. And I was sitting there in Don Nixon's house, listening to him talk to Nixon in the White House about Air West and Hughes. Now, where are those tapes between Don and Richard Nixon? Nixon had Don's phone tapped. Why didn't those tapes come out?"

Left alone, Meier stood a good chance of winning over Domenici, who was thought to be a weak opponent. But in the next five months, before Meier lost in his campaign for the Democratic nomination, he experienced a series of disasters. According to an affidavit by Harry Evans, Meier's campaign coordinator, Tom Benavidez, then a New Mexico senator, was managing the campaign and had his real-estate offices burglarized of Meier's papers, including tax records. Benavidez found a transmitting device on his office phone. The campaign was being directed from that office. Evans' report to Meier on the state's political structure was stolen when someone broke into the Downtowner Motel room in which Evans was staying. (The wire tapping and burglaries by that time were nothing new to Meier. As early as January 27, 1970, he was at the Fontainebleau in Miami with his wife and their room was broken into. Meier's files were taken and he reported the incident to the police.)

Telephone threats on Meier's life became so common that he had to get a police monitor on his phones in an attempt to trace the calls. Although Meier had never met Clifford Irving—and so testified—he was dragged before a Federal grand jury in New York investigating the hoax and subjected to heavy publicity about his possible involvement.

As soon as Meier was cleared of the Irving matter, Summa sued him and others, claiming $9,000,000 had been swindled from Hughes in mining deals.

Then, in May, someone leaked the story to the press that Meier was under investigation by the IRS. Meier had initially come under IRS scrutiny as a result of a massive investigation of the Hughes empire. At the end of 1971, the IRS and the Justice Department—presumably unaware of the depth of the CIA connections to Hughes—sent teams of dozens of volunteer agents into Las Vegas to investigate Hughes-Nevada Operations. The heat was on in Vegas, considering that Intertel, Hughes, IRS, Justice, the CIA and who knew who else were all there spying on one another. According to Hunt's own Watergate testimony, "It was Mr. Bennett who told me that if I ever got out to Las Vegas, to be very careful even of using a telephone booth there; there was so much electronic surveillance out there that he for one would not even trust a coin phone in Las Vegas."

It wasn't surprising. The IRS was uncovering what The Wall Street Journal called the largest skimming operation the IRS had ever seen. In its July 31, 1972, report, the Journal said, "The billionaire was roundly fleeced ... the noose is beginning to tighten." It quoted a "seasoned" Federal agent as saying the situation involved "some of the most incredible swindles I've ever seen" and described the "massive investigative force that is combing Las Vegas, several other U. S. cities and such remote points as the Netherlands and the Dominican Republic."

A minimum of $50,000,000 could not be accounted for right at the outset and all indications were that there were more mysteries where that came from. Spokesmen for the IRS admitted to total bafflement about how business had been conducted in Vegas since Hughes arrived.

Nixon's problem was that some money was intentionally moved in circuitous ways because at least $100,000 had been taken from casinos and passed to Rebozo, earmarked for the White House. The IRS was beginning to turn up bits and pieces of evidence pointing to a Hughes-Nixon relationship and the investigation was immediately flagged "sensitive." In May 1972, less than a month before the Watergate break-in, Roger Barth, assistant to the commissioner of the IRS, reported to Ehrlichman at the White House. He said the IRS had developed information that might embarrass the President (meaning ruin his chances for re-election). The IRS further told Ehrlichman that Donald Nixon's name kept coming up in the Hughes investigation.

The sequence of events leading up to Watergate reads like an invasion plan.

• During January, Meier's Albuquerque home was broken into and bugged.

• During February, there was a break-in at Meier's room at the Marriott Hotel in New York.

• During March, two additional Albuquerque break-ins were made at Meier's

campaign offices.

• Meier's Senate campaign ran from January 11 to June 6, 1972. Less than two weeks before the break-in at Watergate, he lost the primary, his campaign in a shambles.

•

The situation was beginning to get out of hand for Hughes, the CIA and the White House. Even for them, it was an awfully active schedule of larceny.

The three groups had many worries in common. They also had in common E. Howard Hunt, inasmuch as he was employed by Bennett, had been one of the CIA's top clandestine talents and was in 1971 on a daily retainer of $100 from the White House to do special projects. Liddy had worked with Hunt before. By late 1971, he was doing "law-enforcement" work for the White House. He had a flair for wild schemes, guns, fast cars and planes. It was Liddy who originally proposed to Mitchell the brutal tactics for sabotaging the Democratic campaign (such as hiring a yacht full of prostitutes to lure Democrats into compromising situations).

Hunt and Liddy had planned to drug Anderson to make him incoherent during a public appearance and thereby discredit him. Every time someone got close to the Hughes connection, he was bugged or burglarized or discredited.

By the spring of 1972, militaristic security actions had become almost a day-to-day business for Hunt, Liddy and their associates. There were at least two failed attempts to break into Watergate (Liddy, in his typical style, had even suggested shooting out a streetlight to give the break-in team the cover of darkness for a job aimed at McGovern's headquarters). Then in late May, the plumbers, under the direction of Hunt and Liddy, entered the Democratic National Headquarters in Watergate for the first time. They placed electronic bugging devices, which were monitored from the Howard Johnson's across the street and reduced to memo form.